My Italian Ancestors

The idea of fate fascinates me: that a thousand tiny decisions–even things that happen before you were born– conspire to lead you down one path in life instead of another.

I started this story by describing the unexplainable pull I have always felt toward Italy, without which it’s virtually impossible that I would have ever met my maritino. Perhaps it’s more of a stretch to think that finding my great-great-grandmother’s wedding ring somehow had an influence on my destiny, but nevertheless, that is how it seems to me. And somehow it made perfect sense when I learned that I was not the first person in my family to pick up and move to Italy. But even more significant is that while my paternal great-grandmother was teaching German and Latin in Florence at the end of the 19th century, my maternal ancestors were working the land not far away.

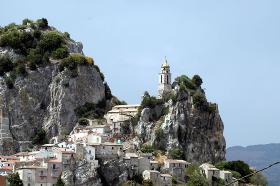

My mother’s mother’s ancestors came from a tiny town in the hills of Molise (the least well-known of Italy’s 20 regions), a place called Bagnoli del Trigno, with less than 500 residents, where everyone knows everyone and most people are related. Two brothers, Enrico and Raffaele, were married to two sisters, Filomena and Michelina.

Life was hard for Italian farmers in the first few decades of the 1900s, and every hand was needed. So even new mothers, like my great-grandmother Filomena, were expected to toil the land. The women who were too sick to work in the fields would have the duty of nursing the children of the village, and this is how Filomena and Enrico’s first-born child died.

The loss of this child was the catalyst that propelled Enrico and his brother Raffaele to seek out a better life. And since America was the land of dreams for southern Italians at that time, that is where they went. Unable to afford passage for all four, the wives were left behind for the time being, and the two brothers sailed across the ocean, arriving, as so many before them, at Ellis Island. It was nearly 1920 and New York was already teeming with Italian immigrants, and besides, Enrico and Raffaele were farmers, so they headed west. They got jobs on the railway, and literally worked their way across the country. They earned enough not only to send for their wives to join them, but also to buy a small farm in eastern Washington state, where my grandmother, Eleanora (whose name was later Americanized to Eleanor) was born in 1922.

This makes me one-quarter Italian. Not very much, when you think about it, but as soon as I learned I was part Italian, at about seven or eight years old, I embraced my heritage whole-heartedly. I would declare proudly that I too was Italian. My sister made fun of me, and loved to remind me that I was not, in fact, Italian, but a boring old American, nothing more. But I felt Italian. I was also part English, German, Irish and Portuguese, but I identified only with the Italian side. Is it any wonder then that I ended up here? And that I can now say that I am, at the very least, Italian by marriage? (Although not yet a citizen; I’ll have to wait a few more years before it’s official.)